There is a quiet generosity to the Turin Film Festival. It doesn’t rush its guests. It lets them speak slowly, drift into memory, lose themselves for a moment. Cinema here is not a performance to be consumed, but a space of listening. Sitting in one of its press rooms, you can feel how easily celebration turns into reflection.

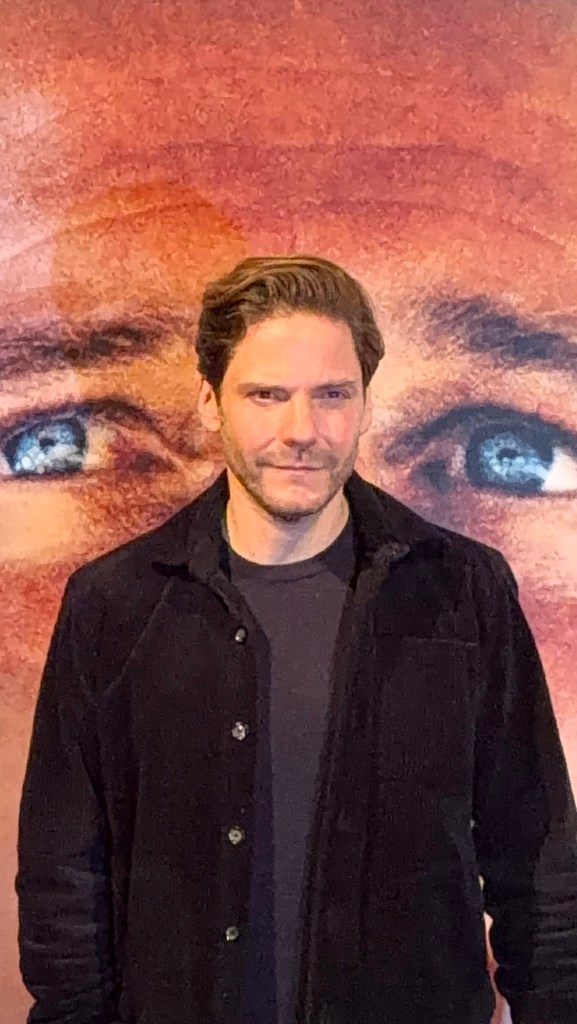

Daniel Brühl seemed to sense this immediately.

Receiving the Premio della Mole at the 43rd Turin Film Festival, he spoke not like someone being honored, but like someone deeply grateful to still belong to cinema. He described the humbling experience of sitting among “legends,” and the encouragement that festivals like this still give him to keep going, to stay curious, to remain vulnerable. There was no distance between the actor and the person. The words came softly, often circling back to fear, responsibility, and trust.

Much of his reflection centered on Rush and the role of Niki Lauda, a performance that pushed him far outside his comfort zone. Brühl spoke openly about the terror of portraying a living icon, about the paralyzing thought that Lauda himself might reject the film. That fear, he explained, made preparation a moral obligation. He needed to spend time with Lauda, to talk with him intimately: not about racing, but about death, fear, vanity. About the things that remain when fame falls silent.

It was in these moments that Brühl revealed how deeply language shapes his work. Raised in a family of mixed cultures (Spanish, German, French), he grew up with borders constantly dissolving around him. Acting, for him, became a way to continue crossing them. Language is not just a technical tool, he explained, but an emotional key. Accents carry posture, rhythm, confidence, even arrogance. Getting Niki Lauda’s Austrian dialect right was not about realism, it was about truth.

This sensitivity to language, to identity, returns again and again in his choices. He spoke of his desire to act in different countries, to inhabit characters before they become icons, to understand who they were before the world defined them. It is why he chose to portray figures like Karl Lagerfeld in French, why he is drawn to rivalries built on admiration and resentment, why he remains fascinated by contradiction.

Emotion surfaced unexpectedly when he spoke of Wolfgang Becker, the director of Good Bye, Lenin!, who recently passed away. Brühl’s voice changed. Becker, he said, was not just a director, but a mentor, almost a second father. Without him, he admitted, he might not be sitting in that room at all. The film’s success, first truly felt outside Germany, in Italy, came as a complete surprise. What they thought would be a small arthouse project became something much larger, deeply human, capable of making audiences laugh and cry across borders.

Throughout the conference, Brühl returned to one recurring idea: openness. He spoke warmly about pop culture and auteur cinema, about blockbuster sets and intimate films, about formula and originality. He has no prejudice, he said: only a desire for sincerity. The greatest gift, for him, is working on something truly original, something exhausting, demanding, uncompromising. Cinema that leaves you standing under the shower at night, knowing you gave everything, without regret.

That feeling, of having gone all the way, seems to resonate with the Turin Film Festival itself. In a world increasingly dominated by speed and judgment, Turin offers something rarer: time. Time to speak, to doubt, to remember. Watching Daniel Brühl speak here, openly and without armor, one understands that this festival is not just about films.

It is about the fragile courage it takes to keep believing in them.