There is something deeply reassuring about the Turin Film Festival. Year after year, it resists the temptation to become louder than the cinema it celebrates. It remains a place where films are watched seriously, where conversations take their time, and where artists are invited not just to promote work, but to reflect on why they do it at all.

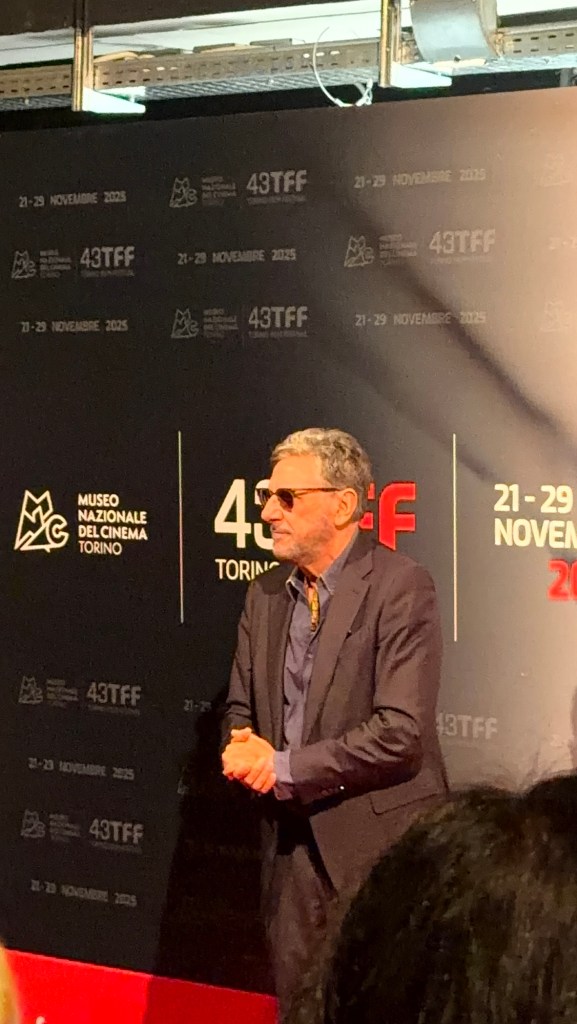

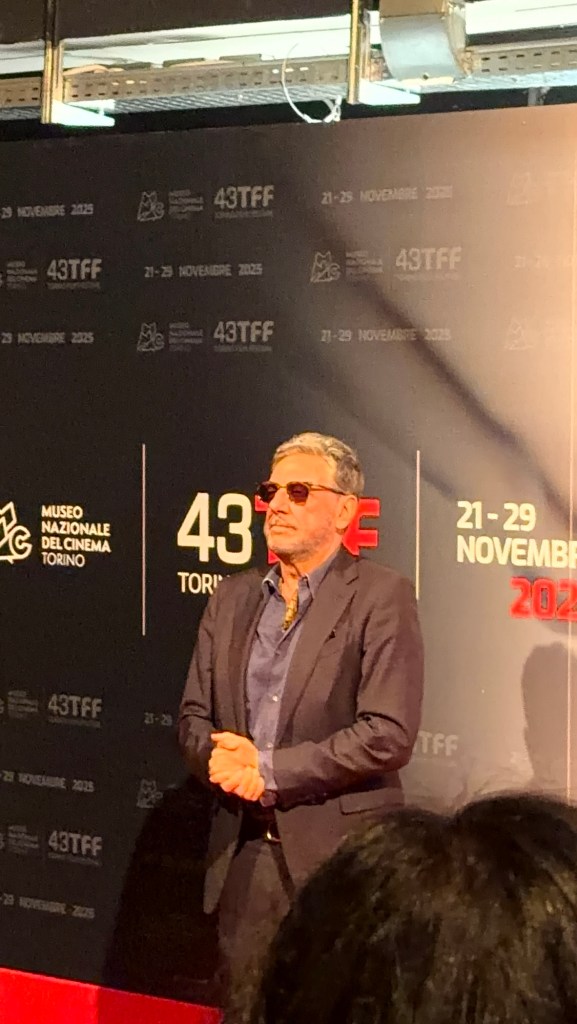

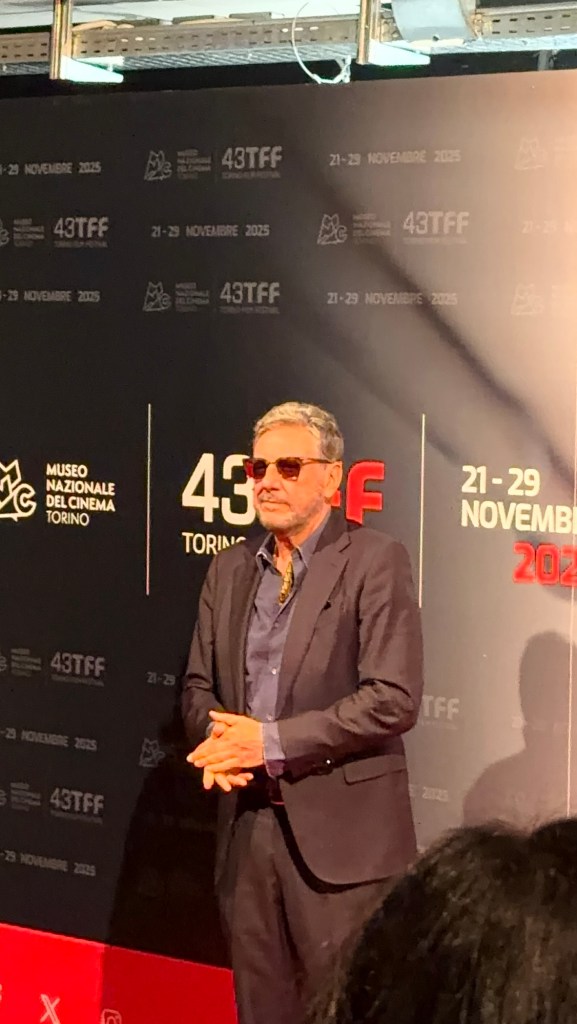

Sergio Castellitto’s presence at the 43rd edition of the festival, where he was awarded the Premio della Mole, felt perfectly in tune with this spirit. His press conference did not unfold like a retrospective victory lap, but rather like a confession: fragmented, thoughtful, and occasionally fragile. What emerged was not the portrait of a celebrated actor looking back, but of an artist still questioning himself.

Castellitto spoke about a period in his life when professional success in cinema coincided with inner difficulty. Despite meaningful roles and recognition, he felt the need to return to theatre; not as an escape, but as a necessity. Theatre, for him, is a kind of shelter, a “den,” a place where words are stripped of protection and must survive on their own. From this need was born a monologue centered on a man who gradually loses everything: social ties, stability, recognition, even himself.

Listening to him describe this work, it becomes clear that solitude is not merely a theme, but a lived condition. The monologue is not just a performance, but an act of exposure. Without fellow actors to lean on, Castellitto becomes both storyteller and witness, relying only on memory, instinct, and the fragile balance between control and error. He speaks of mistakes not as failures, but as openings,moments where truth can unexpectedly surface.

The character he embodies has followed him for years, to the point of becoming almost a presence, a ghost that accompanies him from city to city. Castellitto admits,half-smiling, half-serious, that this figure is always there, even when unseen. Each performance is treated as a first time, because the act of speaking those words is, in itself, a renewal. A quiet confrontation with something unresolved.

When he turns to cinema, the tone shifts but the reflection deepens. Film demands precision, restraint, an understanding of measure. Theatre, by contrast, is alive and uncontrollable. It breathes with the audience, it changes shape, it never allows you to stop. “Theatre is like life,” he says. And in that simple sentence lies the reason why it continues to call him back.

His relationship with Turin emerges naturally, without rhetoric. It is a city tied to personal memory: where he met his wife, but also to work, to early films, to a certain idea of cinema built on seriousness and craftsmanship. Castellitto describes Turin as a rare balance: aristocratic and communal, reserved yet deeply human. A city that understands cinema not as spectacle, but as labor and responsibility.

In his closing remarks, he speaks directly to the festival itself, thanking its organizers for preserving its identity during difficult years. He calls the festival a kind of living museum; a space where cinema is not disguised by glamour, but exposed in all its vulnerability. In a time when the film industry feels fragile, even uncertain of its own future, this honesty feels radical.

As he left the press room, the atmosphere shifted almost imperceptibly. The introspection gave way to playfulness. Castellitto stopped by the TFF Social Room, where the formal setting dissolved into a quick-fire exchange—short questions, instinctive answers, no time to overthink.

His favorite film? 8½ by Federico Fellini. A choice that feels less like a citation and more like a declaration of belonging.

The cinema icon he would like to meet? Daniel Day-Lewis, spoken with the quiet respect reserved for those who disappear entirely into their work.

The genre he watches most often? Simply: arthouse cinema, as if no further explanation were needed.

When asked whether he had ever stolen something from a film set, he laughed and admitted: yes, from sets, and from hotels too.

The first film he ever saw in a movie theater? The Magnificent Seven, a memory that still carries the weight of discovery.

A film that made him cry? Don’t Move—“which I made myself,” he added, acknowledging how cinema can wound its creators most deeply.

The question about the greatest ending in film history stopped him for a moment. He refused to choose. Some endings, he said, arrive as a relief; others hurt because you wish the film would never end. Both reactions, he implied, are equally valid.

Cinema alone or with company? With company.

A character he wishes he had played? None. No regrets. No nostalgia for what might have been.

It was a brief encounter, almost casual, yet revealing in its simplicity. If the press conference showed the weight of words and time, the Social Room revealed something else: an artist at ease with his path, curious but unburdened, serious without solemnity. And once again, the Turin Film Festival proved itself to be not just a place for cinema to be discussed—but for cinema to be lived, lightly and honestly, in all its forms.

Castellitto’s press conference did not offer easy quotes or definitive statements. Instead, it left behind a mood: a sense that cinema and theatre are still, at their core, acts of faith. Faith in words that resist time. Faith in the presence of an audience. Faith in the idea that, even in solitude, speaking still matters.

And perhaps this is why the Turin Film Festival continues to matter too: because it listens.