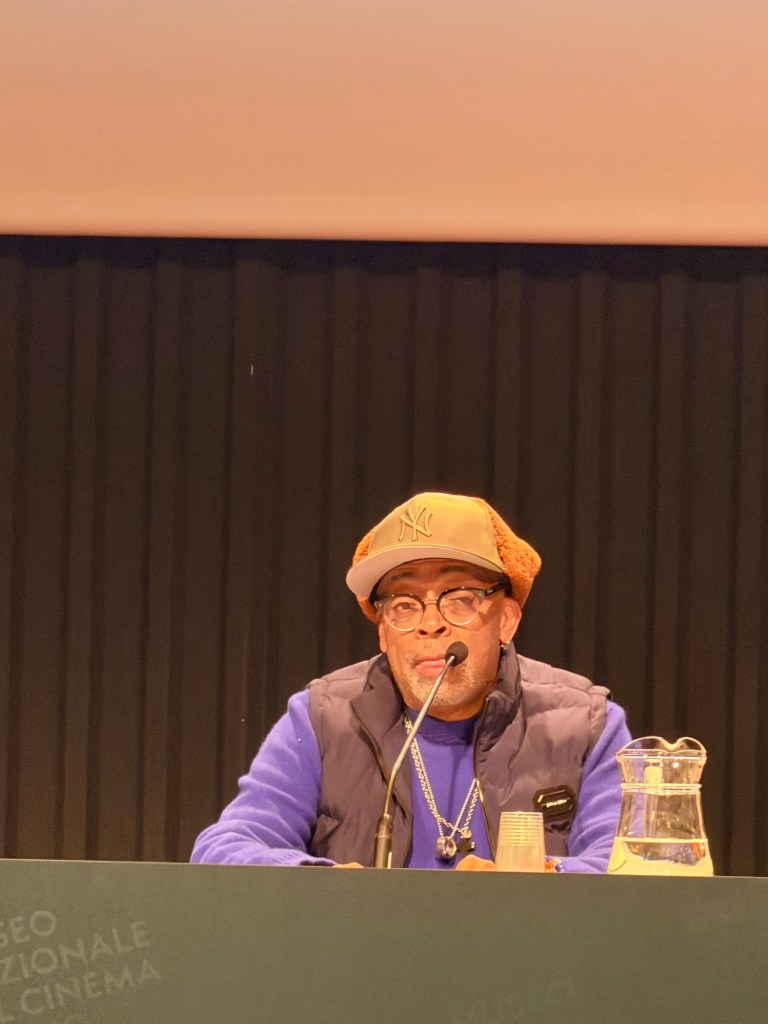

The Turin Film Festival has always been a place where cinema slows down enough to speak honestly. Away from the noise of premieres and algorithms, it offers something increasingly rare: space. Space for memory, for contradiction, for artists to arrive not as monuments but as people. When Spike Lee was awarded the Premio della Mole at the 43rd edition of the festival, that space filled with warmth, humor, and something quietly moving: gratitude.

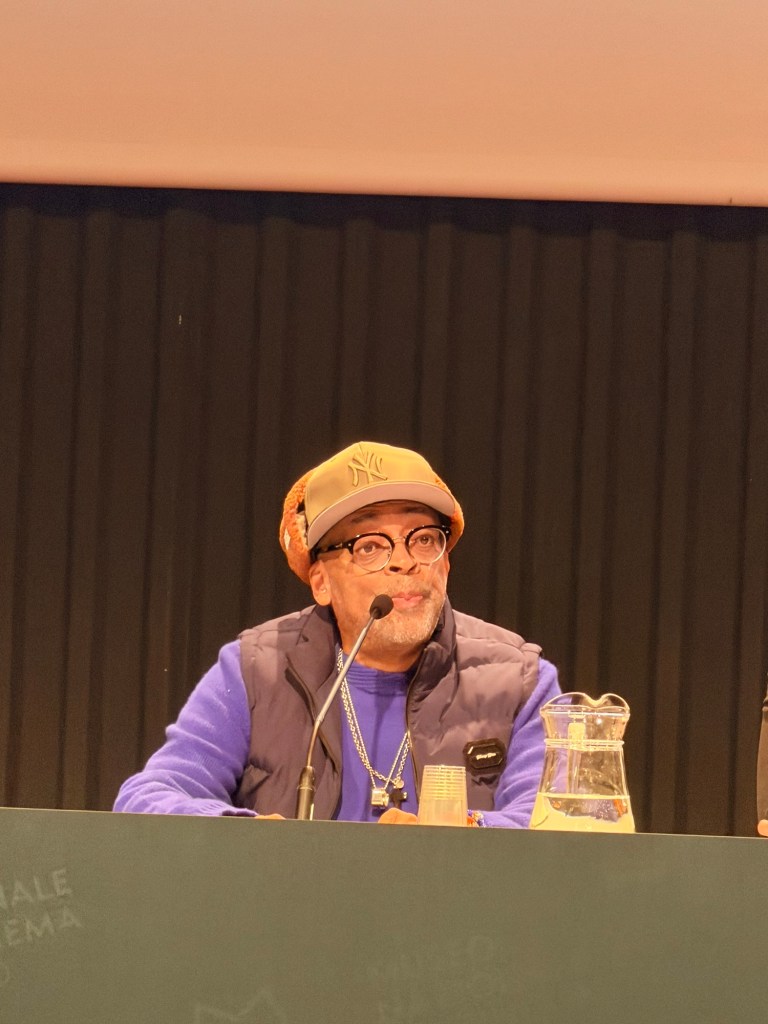

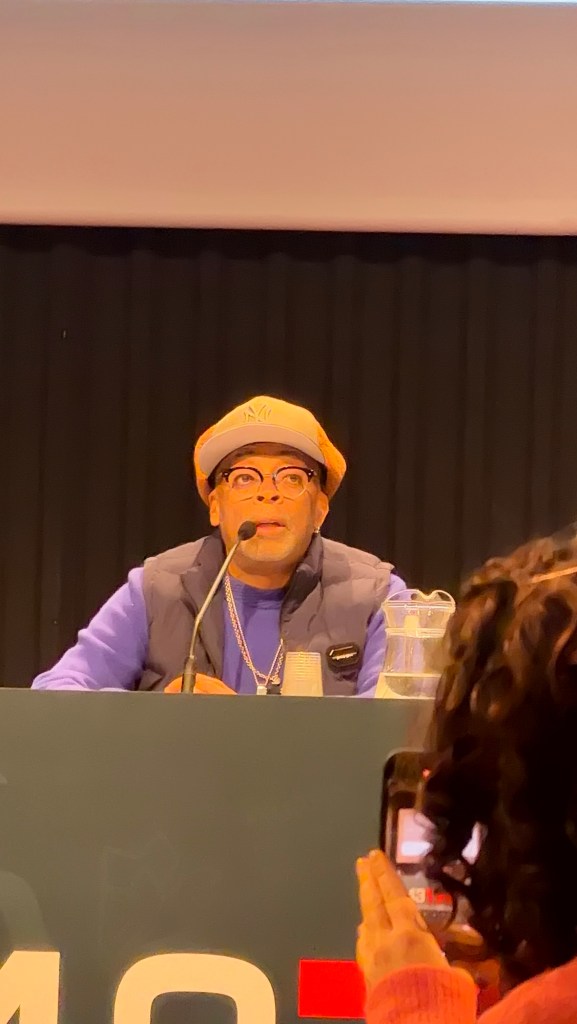

Lee entered the press conference without ceremony, but with unmistakable energy. He spoke the way he makes films: digressive, passionate, grounded in lived experience. Receiving the award, he returned again and again to a simple idea: how lucky he feels to be able to do what he loves. Not in a rhetorical way, but with the conviction of someone who remembers very clearly what it meant to struggle, to be broke, to wait years between projects and still keep going. “If you can make a living doing what you love,” he said, “you’re blessed.” It sounded less like advice than a daily reminder he still gives himself.

The conference moved freely between cinema, teaching, sports, faith, and memory. Lee spoke about his years as a professor, about insisting that his students find what they truly want to do, even if it means being called “crazy” for choosing it. He recalled the early days of She’s Gotta Have It, made with almost no money and enormous faith, pieced together over time with stubborn determination. The film, he reminded the room, nearly killed him; but it also taught him the value of building a body of work, one film at a time, without shortcuts.

There was reverence too. Lee described editing his first film under the watchful presence of Akira Kurosawa, literally. A signed portrait of the Japanese master hung in the editing room, and Lee would turn to it when in doubt, asking silently for approval. He spoke of cinema not as imitation, but as reinterpretation, “a jazz version,” as he put it, where influence is acknowledged, transformed, and made personal.

Amid these reflections, one lighter moment revealed something essential about him. Before arriving in Turin, Lee felt compelled to clarify what some had misread as disrespect: his visible enthusiasm for tennis star Carlos Alcaraz had sparked speculation about rivalry. Lee shut it down gently, explaining his genuine love for sports and then turning his attention to Jannik Sinner. He spoke of admiration, of curiosity, and openly expressed his desire to meet him, to shake his hand, to connect. It wasn’t about celebrity. It was about recognition; one passionate figure acknowledging another, across different worlds.

That moment said a lot. Even after decades of influence, awards, and cultural impact, Spike Lee still wants to meet people who inspire him. He still collects jerseys, still gets excited, still reaches outward. There is no sense of arrival, only continuation.

As the conference unfolded, it became clear why Turin felt like the right place for this encounter. The festival mirrors Lee’s own philosophy: respect the past, fight for the present, stay open to surprise. It does not freeze cinema into reverence; it lets it breathe. It allows artists to speak not only about success, but about fear, doubt, endurance.

By the time Spike Lee left the room, what lingered was not a list of achievements, but a feeling: that cinema, at its best, is built by people who never stop paying attention: to history, to injustice, to art, to joy. And sometimes, simply, to the hope of meeting someone they admire.

In Turin, that hope felt entirely at home.